#WeChooseReuse: Waste Trade and the importance of moving from single-use plastic to reuse

Levels of plastic production, consumption and use are hugely damaging. Reuse measures will enable their reduction, writes Lauren Weir, Ocean Campaigner at the Environmental Investigation Agency.

Levels of plastic production, consumption and use are hugely damaging. Reuse measures will enable their reduction, writes Lauren Weir, Ocean Campaigner at the Environmental Investigation Agency.

The #WeChooseReuse campaign, the objective being to replace single-use plastic with reusable systems and products, has many different facets. Whether that be consumer choice at the individual level, different business refill systems and deposit return schemes to policy facilitating this transition at scale. But all amount to one objective: the clear reason for this campaign being that levels of plastic production, consumption and use are hugely damaging, and these measures will enable their reduction.

In tandem we are also calling on Europe to responsibly manage the treatment of its plastic waste, including through banning shipment of extra-EU plastic waste exports[1] – an irresponsible practice under the guise of recycling that in fact creates immeasurable harm to society, health and the environment[2]. This is felt particularly in countries in the Global South, who are the major recipients of this EU waste destined for “recycling”, despite having infrastructure that is overwhelmed resulting in European plastic waste that should be recycled being incinerated, landfilled or illegally dumped.

“Waste colonialism is an environmental justice issue, Europe is dumping its plastic waste onto others whilst touting itself as an environmental leader.”

A recent Greenpeace investigation helped document this occurring at scale in Turkey, finding UK plastic waste[3] and German plastic waste[4] destined for recycling illegally dumped. In 2020 alone they legally exported 210,000 and 136,000 tonnes of plastic waste to Turkey respectively. To better comprehend the scale of the issue, in combination, Europe sends approximately 241 truckloads of plastic waste to Turkey per day[5]. A country where an OECD Environmental Performance Review has reported it sends 90% of its waste to landfill[6].

We have identified a solution in the form of 5 key recommendations:

| Rethink Plastic Alliance Waste Shipment Regulation Recommendations (for Plastic Waste) – Ban on plastic waste exports outside of the European Union – Fully implement the Basel Convention within Europe to increase transparency and allow for prior informed consent – Establish a clear distinction between mechanical recycling and any other kind of recovery for treatment operations, like chemical recycling, to in turn apply the waste hierarchy – Set a European-wide threshold for waste contamination of 0.5% to improve the quality of the recyclate – Ensure publicly accessible access to waste trade data to facilitate monitoring, enforcement and accountability |

But how are our #WeChooseReuse campaign and our plastic waste recommendations[7] interlinked? And how will eliminating plastic waste exports facilitate reuse systems and lead to plastic reduction?

If Europe were to take full responsibility of its plastic waste treatment it will reduce the risk of plastic waste leakage[8], enhance circularity, and operate within Europe’s finite recycling sector[9] – facilitating reduction and subsequently paving the way for reuse.

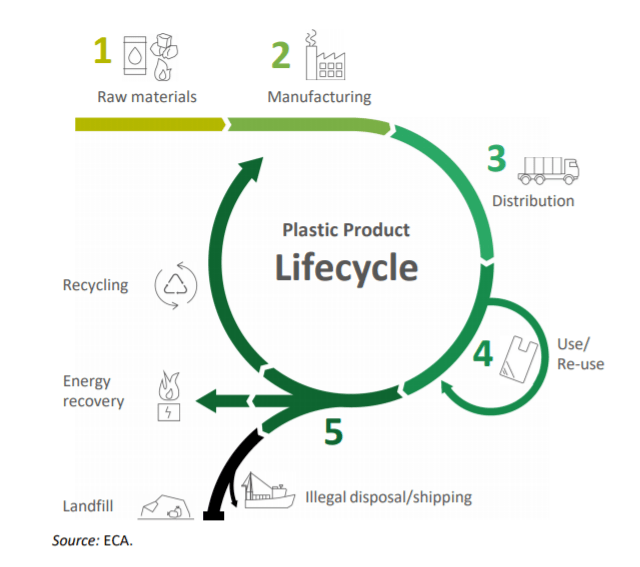

Figure 1 – Exports and shipments, like waste to energy recovery, landfill and incineration, are an externality to a circular economy. Source: https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/RW20_04/RW_Plastic_waste_EN.pdf

Simply put, the export of extra-EU plastic waste is a result of Europe’s overconsumption of plastic and single-use economy. Therefore, Europe needs to export its plastic waste as it fails to handle the majority of it in an environmentally sound manner. For instance:

- Energy recovery is the most common method of treating European plastic waste, followed by landfill. Only approximately 30% of all the generated plastic waste is collected for recycling and recycling rates by country vary a lot[10].

- In 2018 the EU exported 6.5% of all plastic waste collected, the equivalent of 20.2% of all plastic waste sent to recycling facilities[11].

- Between 2012 – 2017 approximately 30% of all plastic packaging waste destined for recycling was exported[12]., the largest volume of plastic product put on the European market that is also principally single-use[13].

- For context, in 2019 this amounted to the EU exporting a monthly average of 150,000 tonnes of plastic waste[14] and not all of this waste is actually being recycled.

- The European Parliament states that the production and incineration of plastic emits about 400 million tonnes of CO2 globally per annum, a part of which could be avoided through better recycling but principally reduction[15].

Dumping European plastic waste in the form of exports is convenient[16], cheaper and a form of greenwashing[17], as this practice is externalising many costs that Europe is responsible for[18]. Europe uses these exports to then state it’s achieving its often over-estimated recycling objectives[19]. Despite this, it seems the EU target of 50% of all plastic packaging should be recycled by 2025 will still not be met[20].

This is further facilitated by the illegal shipments of plastic waste[21]. The illegal EU waste trade annual revenue ranges between 4 and 15 billion euros (midpoint figure of 9.5 billion)[22]. The illegal shipment of plastic waste, end-of-life vehicles and e-waste are expected to increase[23]. Least transboundary movement of waste facilitates transparency and reduces the risk of illegal shipments[24].

Europe has been able to continue consuming high levels of (principally single use) plastic because it knows it can export the problem of its treatment elsewhere, either through currently legal channels or unaccounted illegal shipments. By stopping exports, and accounting for European recycling targets, current recycling capacity and the Commission’s acknowledgement of the need of incineration moratoriums[25], Europe is in turn acknowledging the need for and would need to enact a further absolute reduction in plastic consumption. Consequently, by maintaining waste produced, linearity of production to disposal would be somewhat halted, facilitating circularity.

Operations and consumption of products that currently rely on plastic, including in the form of single-use packaging, would continue. In turn providing the opportunity and demand for reuse and refill to be adopted at scale – the only viable replacement to our current throwaway culture. The subsequent necessity to find an alternative to single use reduces the risk of investing in new reuse/ refill systems which is not without lucrative market opportunities[26].

Like many policy areas, methods and measures are dependent and overlapping. Concurring measures on limiting incineration, reducing the contamination of plastic waste so intra-EU waste trade has better quality recyclate, ensuring eco-design and being wary of the widespread uptake of chemical recycling[27] and biodegradable/ compostable plastics would facilitate success.

Crucially, it is important to note, that neither the methods nor logic outlined above is novel. Bans are common policy measures to heighten the development of a commodity[28] or used to ensure environmental protection[29]. Europe is fully aware of its waste problem and currently has the opportunity to heighten responsible management.[30] In fact, it has already enacted a partial plastic waste trade ban exceeding current international regulations – having banned the export of unsorted plastic waste to non-OECD countries at the beginning of 2021[31].

It must also be noted that a European plastic waste ban would not be occurring in isolation. A number of countries who have historically been receiving this plastic waste have in turn placed import bans themselves as they acknowledge the damage these shipments bring[32]. This was kick-started in 2018 when China[33], as the principle importer of other countries’ plastic waste, put in place an importing ban leaving Europe scrambling to find other destinations for these shipments. The most recent country to place restrictions being Turkey[34].

The ban of extra-EU plastic waste is simply Europe taking an additional step, getting us closer to the tipping point from single-use plastic to reuse existence.

[1] https://www.breakfreefromplastic.org/the-plastic-waste-trade-manifesto/

[2] https://eia-international.org/report/the-uks-trade-in-plastic-waste/

[3] https://www.greenpeace.org.uk/resources/trashed-plastic-report/

[4] https://www.greenpeace.de/zugemuellt

[5] https://www.greenpeace.org/international/press-release/47759/investigation-finds-plastic-from-the-uk-and-germany-illegally-dumped-in-turkey/

[6] https://www.oecd.org/env/country-reviews/Highlights-Turkey-2019-ENGLISH-WEB.pdf

[7] https://rethinkplasticalliance.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/rpa_waste_shipment_regulation_recommendations.pdf

[8] https://wastetradestories.org/

[9] Recycling is necessary but should not be the primary objective, and subsequently drastically enhancing Europe’s recycling ability is a false solution. Plastic can only be recycled a very few number of times (sometimes only once or twice – recyclability rate/ downgrading ultimately depends on plastic type, level of contamination, the nature of the product it is recycled into). Regardless. Polymer breakdown is countered by mixing with virgin plastics. Source: https://www.foodpackagingforum.org/fpf-2016/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/FPF_Dossier08_Plastic-recycling.pdf.

[10] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20181212STO21610/plastic-waste-and-recycling-in-the-eu-facts-and-figures

[11] https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/RW20_04/RW_Plastic_waste_EN.pdf

[12] https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/RW20_04/RW_Plastic_waste_EN.pdf

[13] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20181212STO21610/plastic-waste-and-recycling-in-the-eu-facts-and-figures

[14] https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/the-plastic-waste-trade-in

[15] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20181212STO21610/plastic-waste-and-recycling-in-the-eu-facts-and-figures

[16] “Half of the plastic collected for recycling is exported to be treated in countries outside the EU. Reasons for the exportation include the lack of capacity, technology or financial resources to treat the waste locally. Previously, a significant share of the exported plastic waste was shipped to China, but with the country’s recent ban on plastic waste imports, it is increasingly urgent to find other solutions.” – European Parliament. Source: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/headlines/society/20181212STO21610/plastic-waste-and-recycling-in-the-eu-facts-and-figures

[17] “EU operators must receive documentation attesting that the treatment (including recycling) of plastic packaging waste in a third country is done under broadly equivalent standards to those in the EU. Nevertheless, the European Environment Agency notes that treatment in non-EU countries often causes higher environmental pressure in terms of pollution, CO2 emissions and plastic leakage into the environment, than treatment or recycling in the EU. Verification of compliance with EU plastic waste treatment standards in third countries is often insufficient to ensure respect of EU standards. Member State national authorities have no control powers in third countries and extended producer responsibility organisations, which are responsible for plastic packaging waste management, rarely perform on-the-spot checks. This translates into a low assurance relating to recycling outside the EU and significant risk of illegal activities”. Source: https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/RW20_04/RW_Plastic_waste_EN.pdf

[18] Labour rights, poor working conditions, toxicity and leaching through recycling, leakage, residuals, burning dumping and landfill, chemical and microplastic pollution, exacerbating social inequalities to name a few.

[19] https://www.plasticsoupfoundation.org/en/2020/10/high-risk-that-europe-will-fail-to-meet-its-recycling-targets/

[20] https://www.plasticsoupfoundation.org/en/2020/10/high-risk-that-europe-will-fail-to-meet-its-recycling-targets/

[21] Recent examples including transhipments via the Netherlands (source: https://www.endsreport.com/article/1687089/exclusive-ea-investigates-illegal-import-plastic-waste-netherlands-industry-questions-recycling-figures) or illegal shipments from Italy to Tunisia (source: https://zerowasteeurope.eu/2021/05/waste-trade-italy-tunisia/#:~:text=In%202020%2C%20Italian%20company%20Sviluppo,with%20little%20chance%20for%20recycling.)

[22] https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/ab3534a2-87a0-11eb-ac4c-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

[23] https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/ab3534a2-87a0-11eb-ac4c-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

[24] In addition to effective monitoring, enforcement and adequate penalty.

[25] https://resource.co/article/european-commission-warns-incineration-could-hamper-circular-economy-11632

[26] https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Blog-3_the-path-towards-new-product-delivery-models.pdf

[27] https://www.eunomia.co.uk/reports-tools/final-report-chemical-recycling-state-of-play/

[28] https://unctad.org/system/files/non-official-document/suc2017d8_en.pdf

[29] https://www.businessinsider.com/environmental-rules-laws-protections-around-the-world-2019-4?r=US&IR=T#the-european-union-has-committed-to-banning-pesticides-that-are-dangerous-to-bees-4 and https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/ocean-plastic-pollution-solutions

[30] Currently Europe is revising a host of waste legislation, including the Batteries Regulation, Waste Framework Directive, RoHS Directive, WEEE Directive, ELV Directive, Packaging and Packaging Waste Directive, Waste Shipment Regulation, POPs Regulation (waste annexes)

[31] https://ec.europa.eu/environment/news/plastic-waste-shipments-new-eu-rules-importing-and-exporting-plastic-waste-2020-12-22_en

[32] Bangladesh, Malaysia, Vietnam, Hong Kong, South Korea for instance all have or are looking at restricting imports.

[33] https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/6/eaat0131

[34] Ban on HDPE, LDPE imports May 2021 (Source: https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2021/05/20210518-10.htm) and change of import rules in March 2021 and December 2020 (Source: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1aBExN7txopbWeEQbt9KXz05yWaTkRnNIZwDTM1r5wj0/edit and https://docs.google.com/document/d/19_WM0XYORz_5qavLgdflomo8ZErnXn6yFCCVZITxcf4/edit)