Plastic Free July: a wake-up call for corporations and businesses

Will Europe’s new plastic directive make a global difference in plastic pollution?

By Delphine Lévi Alvarès

Originally published by the global movement #breakfreefromplastic

Last month, people all over the world took the opportunity to celebrate Plastic Free July – taking selfies with reusable straws or bottles, sharing tips on how to avoid packaging by DIY beauty or cleaning products, and bringing reusable containers and cutlery when eating out.

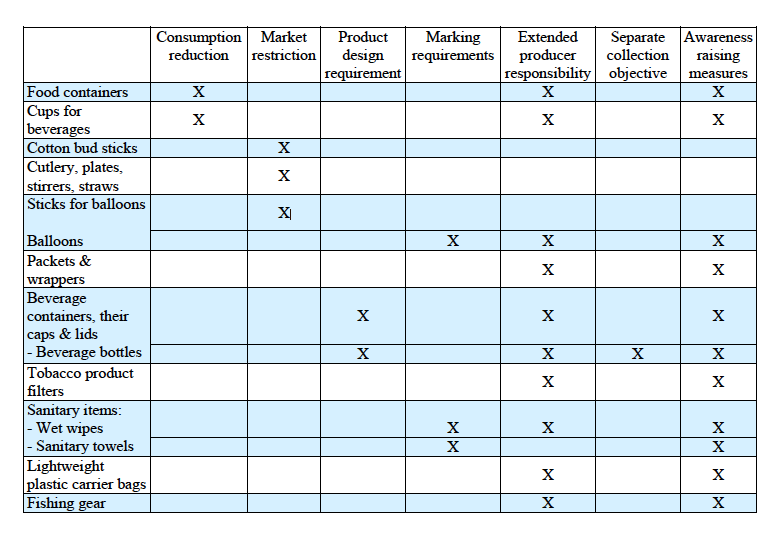

These simple actions to cut plastic pollution have been elevated to a new dimension thanks to the recently tabled European directive “on the reduction of the impact of certain plastic products on the environment”. In this legislative proposal, the European Commission lays out measures to tackle the most commonly found items found from European beaches after decades of citizen and scientific monitoring. All the most notorious items of the plastic free July are there, together with a range of measures envisaged to tackle the issues related to these products.

If you have been following #plasticfreejuly it seems quite obvious that the main solutions are often as easy as a child’s play: refuse, do it yourself, use reusable alternatives and bring refillable containers. So why do we need regulation? Because solutions are still far from being mainstream, and the reusable option is still too often unavailable or more challenging to come by. Alternatives should be made more uniformly available, easier, and more affordable to allow for a greater number of people to be able to embrace a plastic pollution free lifestyle. Companies should stop producing problematic items, because as long as these are widely sold, they will be bought.

The Rethink Plastic alliance – the EU policy arm of the Break Free From Plastic global movement – started campaigning on the plastics issue in 2016. During this time, we called for regulation on the most polluting items and European decision makers kept telling our policy officers that “Europe cannot start regulating people’s bathrooms and kitchens” and that tackling specific items was so symbolic that it was almost ridiculous.

And still, after a year and a half of campaigning, here it is, a beacon of regulation to tackle the most problematic single use items! This is definitely a leap forward in the battle against plastic pollution. After decades of blindness and timid measures, this is a sign the European Commission is waking up to the call from the citizens of Europe, and working to ensure Europe is finally doing its part to solve this global crisis.

But is Europe’s reduction of single-use plastics and increase of recycling going to make a global difference in plastic pollution?

The answer is yes, but it requires a deeper look. For one: It is certainly going to make a difference to the total amount of waste ending up in the environment and in particular, ocean plastic pollution. Second: The move is also a strong symbolic statement against our throwaway society, that could help mainstreaming a smarter lifestyle in Europe and spreading the message outside our borders that our current model of consumption has to change. However, European decision makers, both legislators and business leaders, have to face the absurd reality of the double standards that European businesses are applying abroad. Whilst they appear to be on board with the idea of new Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes on problematic products, they are still more inclined to point at the global South as polluters, and support false solutions such as incineration or short term actions like cleanups, than to acknowledge their responsibility in creating this pollution.

The same companies opening markets in Europe with the “Green Dot” symbol indicating they have financially contributed to the waste collection and managements costs, simultaneously open markets in Asia without contributing to the end-of-life handling costs of these products. Furthermore, there is no Producer Responsibility Organisation (PRO) holding companies accountable for the recyclability of their packaging or products, meaning, they are putting the same product from the same brand in two different kind of packaging. For example, the same shampoo that comes in an easy to collect and recyclable 750mL bottle in Europe, is put on the Asian market in a small format, multilayered sachet which is extremely difficult to collect and even more so to recycle. These sachets are prolific in communities across Asia and the companies are not required to contribute to the costs or meet any recycling target. Companies like Unilever and Procter & Gamble have been so busy exporting our western way of consumption – with design adjustments to match the different economic realities – that the environmental impact of such packaging has been considered completely secondary.

In the process of exporting these low-value packaging overseas, they also have discovered a formidable marketing tool: sachets containing everything you can imagine (from shampoo, to soup or cleaning products) cover the shelves of any local store, with bright colours and catchy fonts, drawing the eyes and inviting the consumer whilst building “brand awareness” to an ever greater degree. The same consumer also sees these packaging everywhere on the floors, the rivers banks, the beaches and as long as they will not associated with the cause of the pollution, they become another marketing opportunity. And we could argue that it is the same with all the disposable products that EU is targeting today. The Asian and African markets are flooded with these products, and none of the producers contribute to handle their end-of-life disposal or recycling. Additionally, companies invest billions in advertising to convince people that they need their throwaway products. In a recent presentation made by the petrochemicals industry, along with millenials from Europe and US, consumers in the Asian markets are the main opportunity for business growth.

However, whilst it might still look like an opportunity today, consumption patterns are changing in these geographies. Our friends who have been opposing single-use plastics by making “Plastic Free July” their daily life for decades are not alone anymore. A vibrant and growing movement of people refusing plastic and promoting a zero waste lifestyle are being more and more visible. Package free shops are flourishing all over Asia (see examples from Malaysia, China, Philippines) and groups emerge to spread these best practices (like Zero Waste Shanghai). In fact all across Asia,changemakers are working to counter mainstream images of poor Asians drowning in plastic waste. Thanks to their work and the intelligence, it is increasingly obvious that a large chunk of the plastics ending up in the ocean in Asia actually comes from the Western world.

European and American companies find it convenient to put cheap single-use plastic products and packaging on the market, but recyclers in these regions are often unwilling to recycle this low grade, and thus low value, material. Most of the time this packaging is shipped to South East Asia where brokers sell it to family businesses who handle it in unregulated conditions. This had reached such an alarming level that China closed its borders to this category of waste (and several others) last January. This move has had concerning repercussions for the other countries in the region, to the point that Vietnam has also temporarily closed its borders to scrap plastics and Thailand has pledged to start sending plastic scrap back where it came from as part of a crackdown on illegal waste imports.

So, how will the new EU legislation on single-use plastics influence this? The proposal is being discussed in the European Parliament through the summer, and a couple of important votes will take place in October. The Council of the Environment ministers of the European Union will amend the text and is expected to handover their conclusions before the end of the year. It is critical that this process leads to the adoption of a strong legislation to reduce the use of single-use plastics in Europe and better management of plastic waste. However, it would be a missed opportunity to not use this momentum to encourage European businesses to apply the same standards here and abroad when it comes to product design. European public authorities must be incentivised to take responsibility for their plastic waste as part of a necessary self reflective activity following this zero waste motto: if you cannot reduce, reuse, or recycle it, you should not be producing it in the first place.