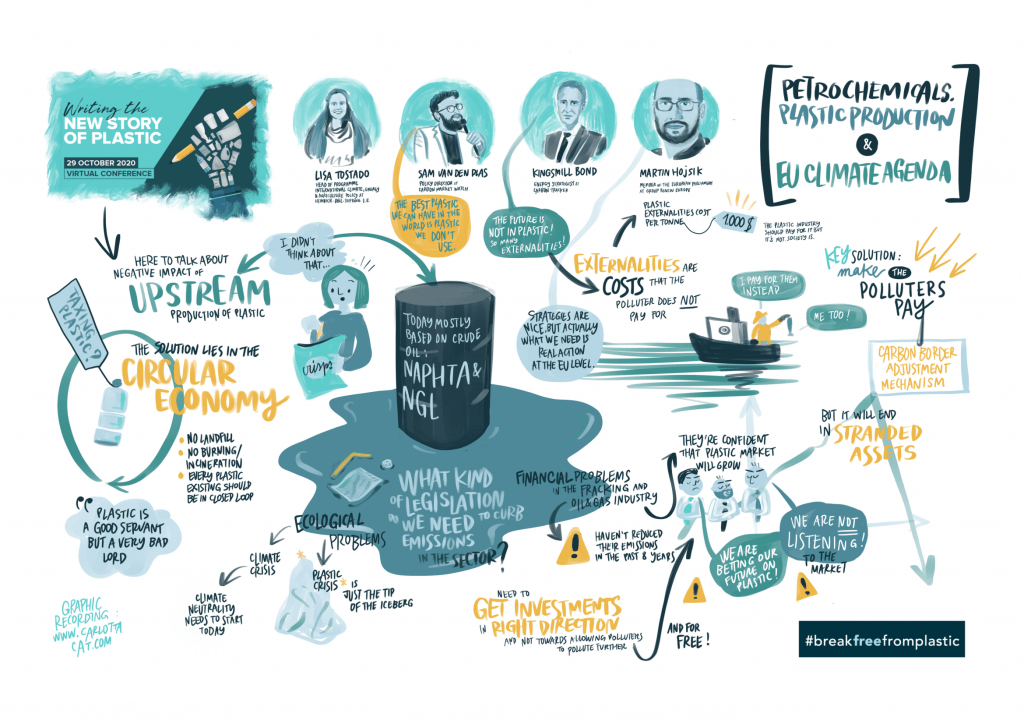

The EU Climate Agenda’s major oversight: the link between the petrochemical industry and plastic production

In our series of virtual panels on Writing the New Story of Plastic, we spoke of the fact that solutions to our plastic crisis have focused for too long on managing end-of-life — where our plastics end up and how we dispose of them once they’re considered waste — and the importance of considering the entire lifecycle of plastic. A significant contributor to our climate crisis and plastic pollution crisis is the very beginning of this lifecycle: the upstream production of plastic.

By Natasha Naayem

In our series of virtual panels on Writing the New Story of Plastic, we spoke of the fact that solutions to our plastic crisis have focused for too long on managing end-of-life — where our plastics end up and how we dispose of them once they’re considered waste — and the importance of considering the entire lifecycle of plastic. A significant contributor to our climate crisis and plastic pollution crisis is the very beginning of this lifecycle: the upstream production of plastic.

Plastics are petrol

The creation of plastic begins with the extraction and processing of fossil fuels, practices responsible for significant greenhouse gas emissions including methane, whose global warming potential is at least 86 times that of CO2 over a 20-year period. While over 99% of plastics are produced from chemicals derived from fossil fuels, the association between fossil fuel extraction and plastic production has slipped from public attention, in large part because the climate impacts of greenhouse gas emissions are more difficult to grasp and less visceral than images of plastic litter flooding our oceans and killing marine wildlife. Yet not only does virtually all plastic come from fossil fuels, the petrochemical industry and the plastics industry are vertically integrated, meaning their prosperity relies on each other. This relationship describes a plastic industrial complex that has flown under the radar of EU policy for too long.

Today, plastics account for 60% of oil demand. As the world relies less on oil and gas and prices for these materials plummet, the petrochemical industry—the largest consumer of oil and gas globally—is hedging its bets on plastics, with plans to double production capacity in the next 20 years. Yet public pressure on plastics is unlikely to yield the kind of demand to match the industry’s intended supply. In addition to the ecological problem of the upstream of plastic production, this gap has the potential to create an even greater economic problem than the one we already face—resulting from the crucial blind spot EU policy and legislation has on this sector, despite the EU’s plan to decarbonise its economy through policy like the European Green Deal.

An industry polluting with impunity

As things stand, plastics impose a massive untaxed externality on society. “Externalities are a real cost, and people pay for them with their lives and with their livelihoods,” says panelist Kingsmill Bond, Energy Strategist at Carbon Tracker. The problem is that the ones paying these costs are not the ones pocketing the cash. Carbon Tracker’s recent report reveals that plastics cost taxpayers 1,000 USD per tonne produced, which amounts to 350 billion dollars of taxpayer money a year. While the principle that polluters should pay these externalities is present in European law, this principle is far from respected, particularly when it comes to industrial decarbonisation. Industries like the petrochemical industry have not reduced their emissions at all since 2012, despite the EU’s climate goals and our ongoing climate crisis.

Even with the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) in place, the EU’s key tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, more than 90% of all the carbon pollution from these sectors has no price tag. The massive handout of free emissions allowances under the ETS—which represents 6.3 billion tons of CO2 over the next ten years—is “a hidden scandal of European climate policy making,” says panelist Sam Van Den Plas of Carbon Market Watch. It requires immediate attention. This “free” handout of carbon emissions represents 165 billion euros over the next ten years, a cost that will fall to European citizens instead of the industries who profit as a result of their production.

Solutions and EU policy

Internalising these externalities—making producers pay for the cost of their pollution—seems like a simple enough solution. Yet the reason the petrochemical industry has gotten away with such shocking impunity is because they’ve incorrectly convinced policy makers that putting a carbon price on their pollution will drive industry outside of Europe and only further pollute elsewhere. Another straight-forward seeming solution is to curtail the demand for plastics, which will curtail the demand for oil and phase out its extraction and processing. While our society is waking up to the negative effects of plastics, and industries across the board are turning away from them in their supply chain, the plastic industrial complex is wilfully blind to this trajectory. With plans to flood the market in oversupply, the discrepancy between their planned and likely growth is projected to create 400 billion dollars in stranded assets. If the EU doesn’t wake up to the flaws in their legislation and the hidden CO2 costs of plastics stemming from upstream production, there is a real risk that public funding will go towards saving this industry rather than towards implementing sound strategies.

With the Green Deal, the goal of Carbon Neutrality and the increase of emissions target to at least 55% reduction by 2030, the European Commission is taking steps in the right direction, but these are nowhere near sufficient. Today, the EU has many good strategies in place, but these strategies have yet to be enacted through equally good legislation. For panelist Martin Hojsik, member of the European Parliament at Group Renew Europe, the solution is in a circular economy: “We need to create an environment that prohibits industries from going into linear systems and puts investments towards creating circular systems.” All plastics should be part of a closed loop system, which would avoid the production of virgin plastics and the creation of waste that ends up in landfill and incinerators. Creating these kinds of new capacities for plastic reduction relies on public money, which is why there is currently a big push to use COVID-19 recovery funds towards these kinds of initiatives.

Carbon pricing and a system like the ETS are no silver bullets to our climate and pollution crisis. In addition to carving out a path towards a circular economy, the EU needs multiple instruments working in unison towards this goal. Instruments such as the Industrial Emissions Directive, the Circular Economy Agenda, the Methane Strategy, and the Carbon Border Adjustment have the potential to be harmonised towards the creation of a climate neutral economy, in which all free emission allowances are phased out, and pollution from plastics is tackled from both ends of the spectrum.