Why are we talking about this right now?

On December 23rd, the European Commission published a proposal for the introduction of EU-wide End-of-Waste (EoW) criteria for plastics as part of an overall Package to Accelerate Europe’s transition to a circular economy, with a specific focus on the circularity of plastics. The package aims to answer Europe’s plastic recycling industry’s struggles, and defines a first set of measures to accelerate Europe’s transition to a circular economy. Further proposals are expected in the upcoming Circular Economy Act, which aims to create a Single Market for waste and Secondary Raw Materials. The EoW criteria proposal from December lays the groundwork for transitioning towards a European market for recycled plastics. But as it stands, the proposal has gaps, especially on chemicals, which will undermine the long-term circular economy in Europe and beyond. To address these gaps, the Rethink Plastic Alliance made concrete recommendations in our RPA response to the Commission’s consultation.

What is the idea behind this proposal?

To support its transition to a circular economy, the EU wants to boost the use of waste-derived materials, also commonly referred to as “secondary raw materials”. In practice, this means that new products should preferably be made using recycled materials to reduce primary materials extraction. Currently, of the approximately 58 million tonnes of plastic produced in the EU, only half is collected and sorted, and only around 13% is recycled into new plastics. One way to achieve this ambition to become the global circularity leader is to double Europe’s circularity rate in the economy to 24% by 2030, by first and foremost championing reduction and reuse measures and by facilitating recycling and the uptake of recycled materials. The current proposal aims to establish a single, harmonised set of EoW criteria to determine when waste ceases to be waste and facilitate the trade and uptake of recycled content.

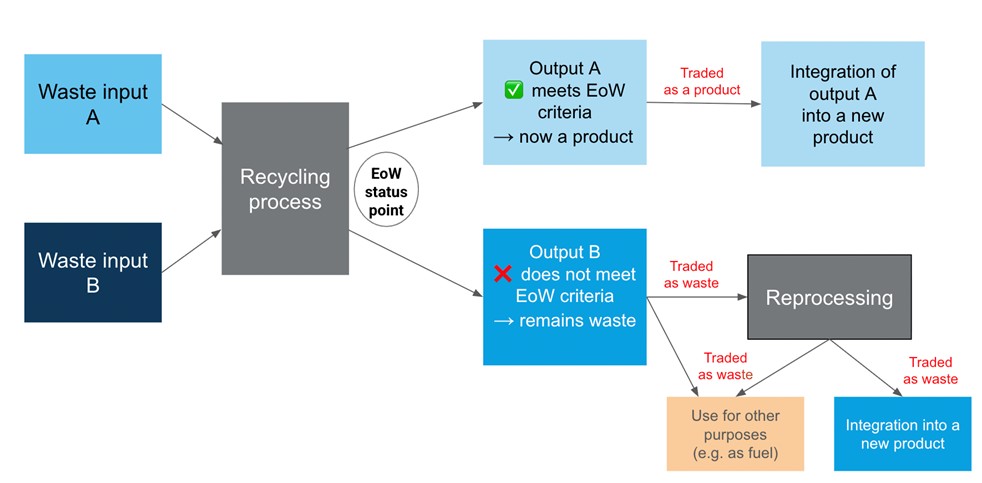

What is the legal significance behind the End-of-Waste criteria?

EoW is a legislative definition setting the moment when a material legally ceases to be waste and becomes a waste-derived material that can be used as a product. This legal change matters: once a material is no longer classified as waste, but as a waste-derived material meeting EoW criteria, another regulatory framework – the chemical and product framework – applies. The legislative regime governing products is usually less restrictive than the one regulating waste. For example, the trade of products, within the EU and outside the EU, is much less regulated than waste trade.

What are the criteria to transition from waste to product?

For the legal change to happen, the material has to meet four criteria defined under Article 6 of the Waste Framework Directive:

- The substance or object is commonly used for specific purposes

- A market or demand exists for such a substance or object

- The substance or object fulfils the technical requirements for the specific purposes andmeets the existing legislation and standards applicable to products; and

- The use of the substance or object will not lead to overall adverse environmental or human health impacts.

Such criteria are material neutral, and the EU has defined, for a number of materials, more specific EU-wide harmonised criteria applying across the EU. The current proposal focuses on EU-wide criteria for plastics.

What does this mean in practice?

- Setting the ground for a European recycling market – the proposal puts an end to the different national interpretations of EoW rules and unifies them at the EU level, which simplifies cross-border trade, supporting the setting-up of EU plastics waste-derived markets.

- Reducing economic costs – without harmonised criteria, the additional administrative and compliance costs for the EU plastics recycling sector are estimated at around €120 million per year, or roughly €260,000 per recycler on average.

- Clarifying legal responsibilities across the value chain – by defining when waste becomes a product, the proposal reduces legal uncertainty along the value chain, which supports the development of the new markets.

What does this proposal cover?

The proposed EoW framework applies to plastic waste that was addressed by either mechanical recycling or solvent-based processes. These processes do not change the chemical structure of the plastic material. Technologies falling under the umbrella concept of ‘chemical recycling’ remain outside the scope of the proposal, reflecting the need to further assess their respective efficiency and added value to the circularity of the plastics sector.

How does it impact waste trade?

Waste-derived materials granted EoW status can be traded, within and outside the EU, with far fewer controls than waste and waste-derived materials not granted EoW status. If EoW criteria are too weak or not effectively enforceable and enforced, certain operators could exploit EoW policy to misdeclare waste as a product and escape plastic waste trade regulations, including the upcoming ban on plastic waste exports to non-OECD countries. It is therefore essential to set strong criteria, including waste input restrictions and strict contamination limits, so that facilitating the trade of recycled materials does not undermine regulation on harmful waste trade practices.

A broader perspective on circular economy: going beyond recycling

Taking this proposal into the broader context of its proposal (i.e. Mini Circular Economy Act Package), the EoW proposal aims at transitioning from 27 national recycling markets for plastics waste towards a single EU market. The deepening of the EU level is mirrored by the introduction of Trans-Regional Circularity Hubs, in line with the deepening of the internal market. However, for these hubs to fully deliver their potential to transition towards a circular economy, theyneed to embed other economic activities like reuse, repair, refurbishment, and remanufacturing. Reducing waste generation in the first place will support closing the circle and reducing pollution.

Equally important and necessary in the transition towards a circular economy is to urgently tackle the issue of toxicity. In other words, it means that actions should be taken at the upstream level to remove hazardous chemicals already at the design stage. It is worth noting that there is currently a lack of coherence between chemical and circular economy legislation. In this case, EoW acts as an interface between chemicals, products, and waste, which could either bridge or deepen the gap between these three fields of legislation. Therefore, it is key to focus on managing toxic chemicals through an improved product’s lifecycle, to ensure products’ safety and high-quality recycling.

For EoW to bridge the above mentioned gap, it is important that the proposal has strong criteria for eligible waste input. However, the current proposal largely focuses on the output of recycling processes, implicitly assuming that hazardous substances can be removed or neutralised during recycling. In reality, this is often technically unfeasible or regarded as too expensive. Furthermore, emphasising the output of the process could create a counter-incentive: instead of phasing out toxic chemicals at source, producers may rely on recycling to “manage” contamination downstream. For these reasons, it is key to act at the production stage to support the redesign of plastic products that will support safer and more cost-effective recycling, while improving the coherence between circular economy objectives and chemicals legislation.

Introducing an EU-wide EoW framework for plastics is a welcome and necessary development. An EoW framework promises real benefits for recyclers, but to ensure that this progress is lasting, the proposal must be strengthened and complemented by stronger action on chemicals and a broader vision of circularity that goes beyond recycling alone. Only by aligning waste, product and chemicals legislation can Europe truly use resources effectively and strategically, close the loop—and keep it closed.

Notes:

To know more about why setting clear, effective, and enforceable EoW criteria is essential to not undermine waste trade legislation, you can read this blog from our member EIA.