But how “clean” can the Commission’s plan really be if it fails to properly address one of the highest emitting and polluting sectors, and fails to consider toxicity and pollution? Addressing the petrochemical and plastic industry and preparing for a managed phase-down must be part of any serious plan to promote a “clean” European industry.

The plan presented today does none of this, and coincidentally – or not -it was presented in Antwerp, the largest petrochemicals hub in Europe and the second in the world. It was launched in a closed-door event with some of Europe’s biggest polluters, including the biggest chemicals industry lobby, CEFIC. Civil society and communities that have to live every day with the pollution caused by these same industries, were not invited to the meeting. This is an affront to democratic and participatory processes, as well as the impacted citizens.

The Commission has accurately identified the need to decarbonise – and therefore reduce emissions – in key European industries, a crucial step towards reaching the EU’s climate targets and boosting EU competitiveness. Yet the proposal foresees hardly any action to curb Europe’s pollution and toxic contamination crises. In fact, it does not address one of the highest-emitting and highest-polluting sectors at all – namely the plastics and petrochemicals sector.

By designing policies that reduce the production and consumption of plastics and petrochemicals, the EU can take a significant step toward curbing both pollution and GHG emissions, staying on track for its Green Deal commitments while also reaching its stated goals of decarbonisation and competitiveness.

Plastic production is the most energy-intensive sector in Europe

Plastic polymer production is fueling oil and gas demand as 99% of plastics are made from fossil fuels such as oil, gas, and coal. Plastic production has seen major growth over the past decade. The industry’s current growth trajectory is exponential and plastic production is expected to double or triple by 2050. Plastic polymer production could consume up to one-third of the remaining global carbon budget by 2050, even in a decarbonized scenario.

In the EU, plastic production is by far the largest industrial oil, gas, and electricity user, even ahead of energy-intensive industries such as steel, automobile manufacturing, and food and beverages. In 2020, plastic production was responsible for nearly 9% of the EU’s fossil gas consumption and 8% of EU’s oil consumption.

The plastic industry in the EU is looking at pathways to decarbonise its processes, but it is heavily relying on not-proven technologies, such as carbon capture and storage, and chemical recycling. Yet even if the plastic industry were to decarbonise its energy supply, that would not significantly reduce the emissions associated with the plastic industry as 70% of fossil fuels used in plastic production stem from raw material production rather than energy use for processing. Reducing the overall production and consumption of plastics and petrochemicals is the only way to significantly reduce the greenhouse gas emissions linked to plastics.

Plastic production – a pollution nightmare

Increasingly, the building blocks of plastic come from fracked gas in the United States. The pollution and impacts on communities associated with fracking are well evidenced, including water supply depletion, drinking water contamination, air pollution and habitat destruction.

In addition, many chemicals used in plastic production and products are known to be hazardous to human health and the environment, impacting workers and users. For example, exposure to PVC widely used in flooring, pipes, and medical devices, is associated with an increased risk of liver, brain and lung cancers. Several in-depth investigations have revealed the scale of the PFAS pollution crisis across Europe. Next to being an acute danger to public health and the environment, cleaning up this pollution will cost the staggering number of €100 billion each year. Microplastics, and the chemicals in them, reach everywhere in the environment and our bodies, with increasing evidence on the impacts associated.

Why stick to single-use when innovative, cleaner solutions already exist?

The majority of plastics produced are short-lived products and packaging, even though more durable and reusable options are available. At the end of their short yet very harmful life, these single-use plastics create further air, soil and water pollution through inadequate disposal and landfilling, as well as incineration. The plastics industry presents plastics as a circular material, promising recyclability. Yet most (single-use) plastics are not recycled, and contain hazardous chemicals that impair recycling, and end up incinerated.

Even when recycling is possible it is not a closed-loop method as the addition of virgin materials is very often necessary, plastics can only be recycled a short number of times and are often downcycled in another product. Only 30% of plastic produced in Europe is actually recycled – and on a global level, only 9% of all plastics ever produced have been recycled. This shows that the “lifecycle” of plastics is neither circular nor clean and that drastic plastic production reduction is urgent for the EU to achieve its climate and zero-pollution objectives.

What the EU can do to build a fossil-free, toxic-free and resilient Europe

Europe, and the rest of the world, can drastically reduce its production and consumption of plastic in various sectors, as alternatives are already widely available.

Close to 40 % of plastic produced in the EU is used for packaging, most of which for single-use applications, significantly contributing to the staggering 190kg annual packaging waste generation per inhabitant in the EU. The mainstreaming of packaging-free practices and reuse systems across the EU could drastically reduce plastic production and consumption associated with packaging. This is in line with the packaging waste reduction mandated by the recently adopted Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation and would reduce emissions associated with plastic production and plastic and plastic feedstock imports.

To be “clean”, any deal must aim towards the zero-pollution ambition of the EU; this requires detoxifying production processes, products (including plastics), and our economy overall. Yet, the Clean Industrial Deal presented by the European Commission does not mention any intention to tackle (chemical) pollution, aside from referring to a future Chemical Industry package scheduled for the end of the year which appears to largely aim at giving the sector a significant boost. Instead, a strong implementation of the zero pollution action plan and Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability could actually move the EU further away from a toxic-free society.

Reuse has always been part of life, in various forms, allowing products and packaging to be used multiple times for the same purpose. Mainstreaming reuse would maximise its benefits, including reducing resource use, water use, energy use and emissions, while bringing economic value and creating jobs. And we already know they work, because several EU member states have implemented well-functioning systems, for example in the shape of deposit return schemes. In line with the PPWR, member states should invest in the development of these innovative services – an opportunity that could create hundreds of thousands of jobs in the next few years according to the European Commission’s projections.

A strategic use of resources puts an end to dirty deals

The EU imports most of the feedstock for plastic production, notably oil and (fracked) gas from the US and, until recently, a considerable amount of gas from Russia. Europe’s dependence on energy imports became painfully obvious in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Now, the threat of a “trade war” is looming over the EU and exposing its reliance on foreign imports once more. Reducing plastic production and consumption, by supporting the reuse economy, and improving toxic-free recycling, would also reduce the EU’s dependency on unstable partners and support its resilience.

In a context where we have no other choice than to reduce our overall use of resources to remain within planetary boundaries, we have to find a strategic use of those resources. Producing millions of avoidable short-lived single-use plastics is not one. Increasing recycling and recycled content integration and substituting fossil-based feedstock with bio-based feedstock will not do the trick if it is not preceded with drastic reduction in plastic production and accompanied with a shift from short-lived and single-use to long-lasting and reusable products.

There is no financial case for producing this much plastic

Data shows that petrochemical production in Europe has been stagnating, and in the case of plastics has shown signs of decline. This is due to a number of factors, among which are high energy prices, but it is chiefly caused by overcapacity, overproduction and a lack of demand. In addition, consumer attitudes are shifting away from single-use disposable plastic to more durable, less toxic options.

Even though there is no business case for investments in the petrochemical and plastics sector, the Clean Industrial Deal foresees 100 billion-Euro-subsidies to energy-intensive industries. However, a new investigation reveals that these companies already have substantial access to capital. Their financial issues actually stem from a misallocation of resources. These companies, among which petrochemical producers BASF and TotalEnergies, are funneling the bulk of their profits – over 75% – into shareholder payouts instead of investing in making their businesses fit for the green transition.

A “clean” deal should not fuel the profits of highly polluting corporations. Instead, the EU should support real solutions to protect the health of people and the planet.

The EU needs to plan a just transition for the petrochemical industry

According to the industry itself, Europe’s petrochemical market share has been declining: this should be the EU’s opportunity to prepare for and initiate the transition of the petrochemicals and plastic sector in Europe and manage declining production and the already ongoing closure of facilities in a way that is just and fair, especially for workers.

The plastic sector is a poster child of a model based on high resource use, high energy consumption, and intensive chemical use. It is at the intersection of the climate, waste, and pollution crisis, fueled by harmful subsidies and with major impacts on human rights. Yet, it can also serve as a model for a planned and just transition of an industry. By designing this transition with workers, communities, scientists and civil society, supporting reskilling and trainings, the EU has the opportunity to ensure a truly just transition.

Supporting plastic production reduction in Europe and on the global stage

Successfully managing the transition of the plastics and petrochemicals industry in Europe would reaffirm the EU’s support for plastic production reduction on the global stage. As part of a group of 100 countries, the EU and its member states supported a dedicated provision to control and eventually reduce plastic production in an international legally binding instrument, the Plastics Treaty.

By supporting a strategic use of resources by industries through decarbonisation and reduction as well as regulating what is allowed to enter the EU market, the EU can significantly reduce pollution and harm to human health caused by plastic production, in Europe and elsewhere. Supporting reduction measures in the plastics and petrochemical sector could allow the EU to, once again, inspire a leveling up of environmental and social requirements across the world.

Further Resources:

- The Clean Industrial Deal hides dirty concessions” – EEB press release

- Zero Waste Europe calls for stronger circularity measures in the Clean Industrial Deal

- EU Clean Industrial Deal: Some opportunities with few guarantees

- Joint CSO and business demand A “Clean” Industrial Deal that works for the planet and its people

- Clean Industrial Deal – ECOS recommendations

- Can the EU’s Clean Industrial Deal Deliver for the Planet? – Center for International Environmental Law

- EU Commission’s Omnibus proposal is full-scale deregulation designed to dismantle corporate accountability – Corporate Europe Observatory

- Lawyers condemn the Omnibus proposal – a threat to the environment and EU competitiveness | ClientEarth

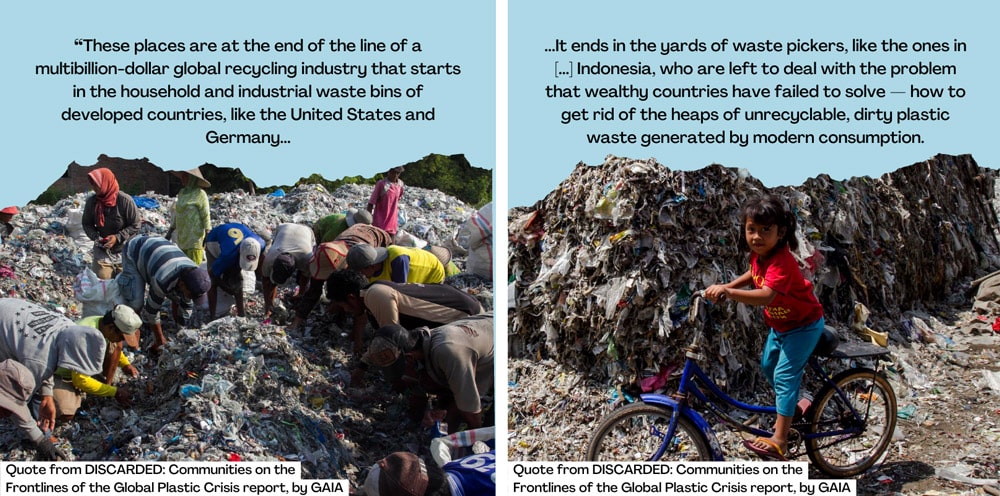

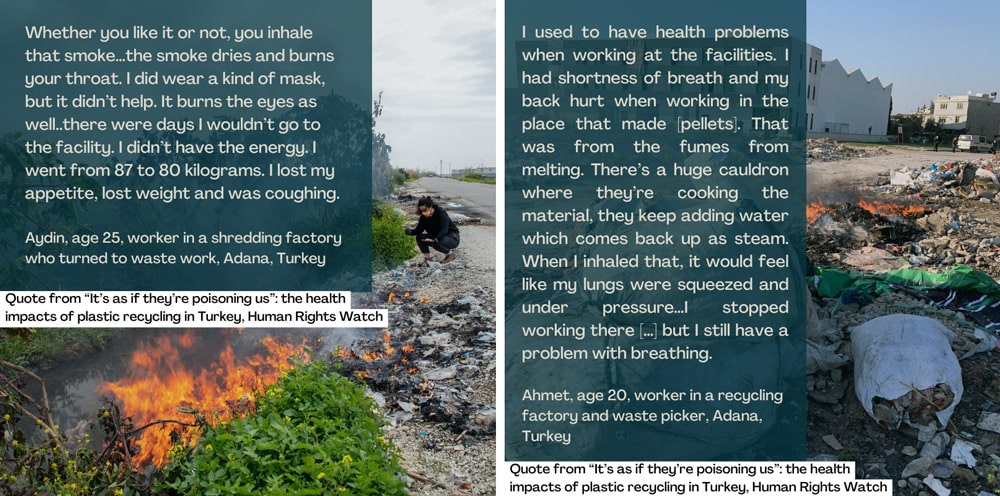

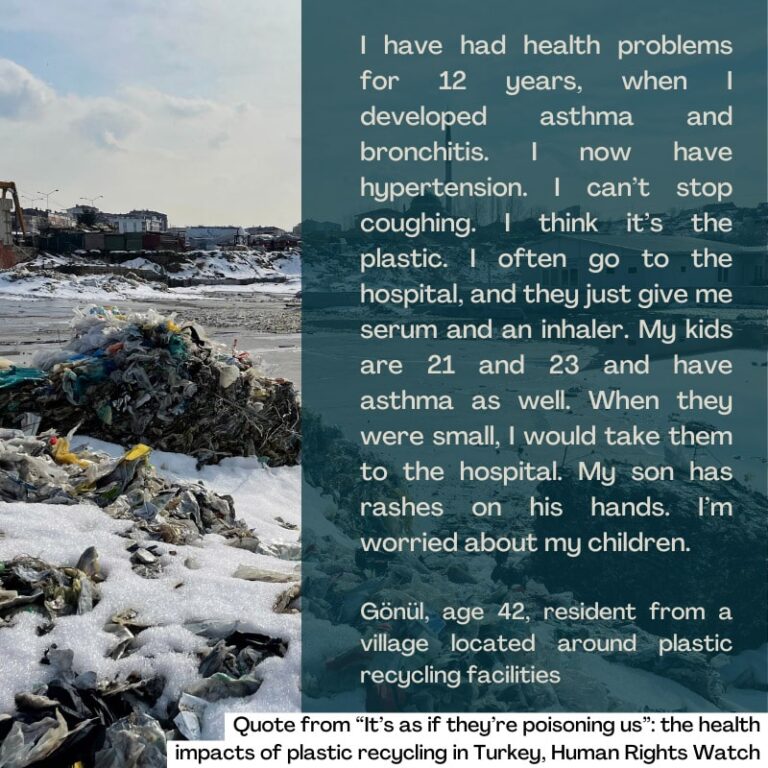

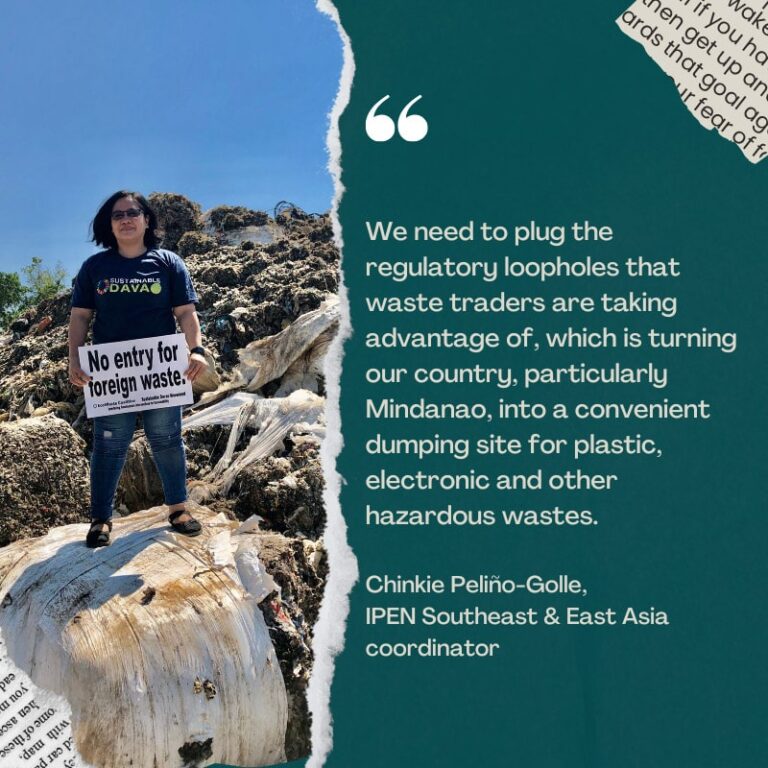

Plastic waste exports can have catastrophic impacts on the environment and human rights, especially the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment. Plastic waste ends up polluting water, contaminating air, and harming the health of people already facing poverty and marginalization. This is a terrible environmental injustice!

Plastic waste exports can have catastrophic impacts on the environment and human rights, especially the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment. Plastic waste ends up polluting water, contaminating air, and harming the health of people already facing poverty and marginalization. This is a terrible environmental injustice!